Ana Tzubery is a licensed foster parent and former journalist, originally from Ukraine, currently residing in California. Influenced by her life experiences in Ukraine and Israel, and now rooted in the U.S., she offers a global perspective in her work with children and parents, focusing on cultural resilience. Ana writes about themes of faith, identity, and the quiet strength of displaced children, giving a voice to those who are often overlooked.

It is April of 2025. The moment I’ve been working toward, speaking about, and pushing for is finally here.

Today, the Department of Children and Family Services of Los Angeles County (DCFS), in partnership with DCFS Faith in Motion and Second Nurture, is hosting an event that brings foster parents together to explore an overlooked, yet meaningful component of childcare: faith. This conversation is aimed at creating an open and honest dialogue on the realities of taking care of children from different faiths, namely from the three Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

This is not about preaching to anyone. The purpose of this moment is to equip foster parents, who often care for children of different backgrounds, with understanding, respect, and support for a child’s spiritual identity. While discussions about religion and faith can be divisive, this panel focuses on empathy, education, and unity.

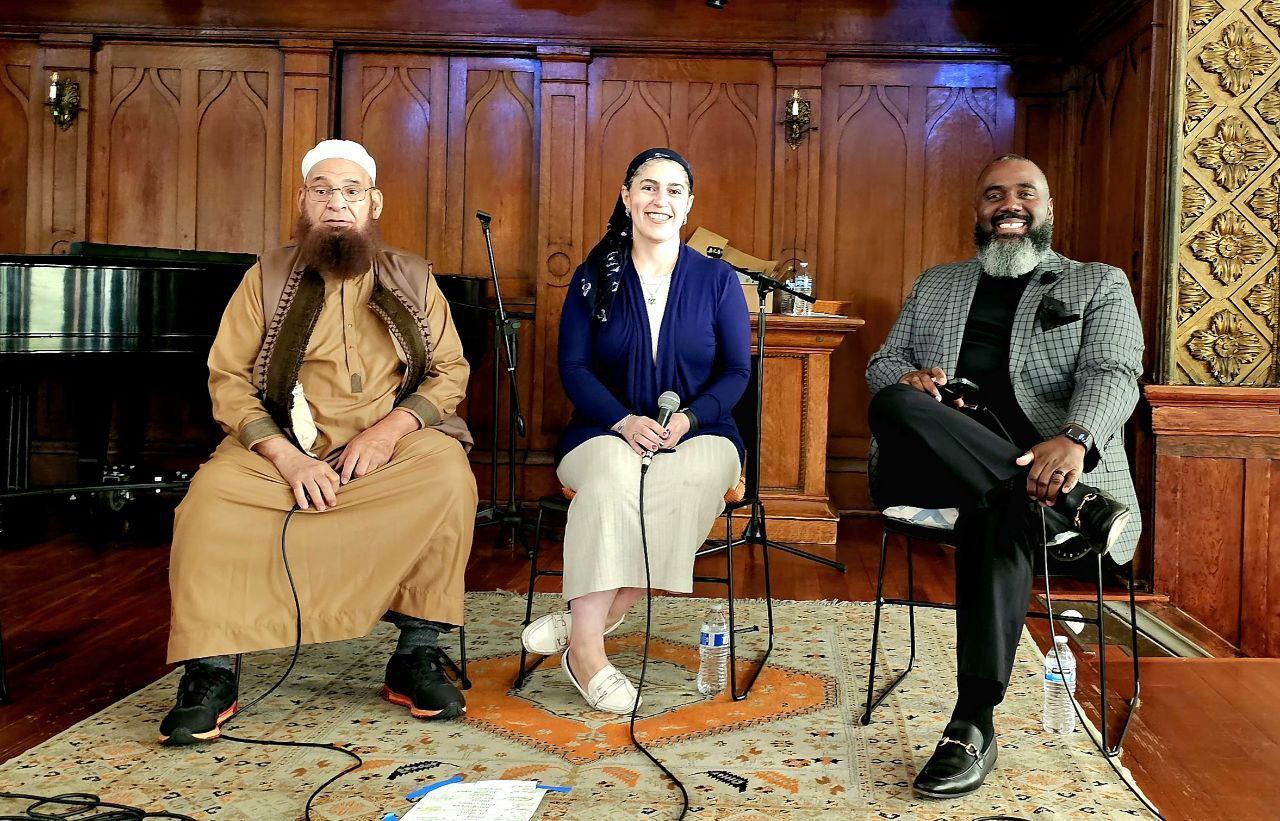

An Orthodox Jewish woman from Iran, a devout Muslim foster father from Libya, and an African American Christian pastor shared their experiences of raising children guided by their beliefs. The panelists provided insight into their faith and culture, emphasizing common ground in their commitment to children in their communities. They all agree on the sanctity of family and the sustaining power of faith.

Common Grounds in Faith and Parenting

The host asked each panelist the same question: Who do you turn to when you’re overwhelmed, when nothing is going right, when you’re exhausted to the bone?

Their answers came in different words, shaped by different traditions, but their core message was identical.

They turned to God.

Then all three speakers highlighted the vital role of structure, consistency, and spiritual grounding in children through the structured rituals of Shabbat in Jewish homes, the daily prayers woven into Muslim family life, or the communal worship found in Black churches… The message was the same: children flourish when they are connected to something greater than themselves.

Structure, they stressed, is not just about rules or discipline. It is about stability, trust, and assuring children that they are not alone. They emphasized that structure is about showing children that someone, whether family, community, or God, will be there to catch them when they fall. Their approach was not based on theory but rather on lived experience. These caregivers had seen the difference. They had watched children blossom when given clear expectations, consistent routines, and spiritual language to make sense of the chaos around them.

The Crisis of Displacement in the Foster System

Too often, the foster care system unintentionally dismantles the very pillars children need most. When children enter foster care, they are not just separated from their home, they are pulled away from everything familiar: the food they know, the language they speak, the customs they trust, and, most critically, the religious rituals that ground them. By creating “neutral” or “safe” environments, many placements end up scrubbing away the child’s cultural and religious identity. This policy of “neutrality” transforms into erasure.

And it bears a steep cost.

For many children, their religion is not just a set of beliefs. It is a daily routine that brings feelings of comfort, stability, and normalcy.

The voice of a grandmother’s prayer or the sound of a song they sang in their mother tongue is integral to the child’s sense of belonging. Stripping away these components of a child’s life, you’re not just disrupting a routine, you’re severing a lifeline. The approach of “neutrality” is not just culturally insensitive; it exacerbates the trauma children experience when they are removed from their home.

Why Cultural and Spiritual Continuity Matters

A Muslim child who no longer hears the call to prayer.

A Jewish child who no longer lights the Shabbat candles.

A Christian child separated from their church family.

When a child’s religious and cultural practices are disrupted, children often experience grief that is overlooked by the adults around them. Their grief is not always obvious, as it does not come in the form of tantrums or behavioral issues. However, the loss is deeply profound. The practices a child loses are not merely ornamental, they are foundational rituals that connect children to who they are, where they come from, and most importantly, their community.

Each may experience grief differently.

Language and food, which are often dismissed as minor comforts, are powerful anchors of identity and emotional stability. A Russian-speaking girl had been placed in an African American household for over six months. What she missed most was not toys or electronics. It was the comfort of drinking tea in the morning, a small ritual that she had practiced her whole life and that reminded her of home. A Farsi-speaking boy who was developmentally delayed and placed with a religiously identical household. He spoke English but remained distanced. The real breakthrough happened only after he began bi-weekly visits with a Farsi-speaking volunteer. The sound of his mother tongue, after his mother passed away, gave him a sense of safety no therapy ever could.

Promoting cultural literacy is important, but it’s not enough. We must go further. We must uphold the right of every displaced child to maintain their unique cultural identity. Allowing a displaced child to maintain their unique cultural identity is instrumental to fostering their emotional development, sense of self, and resilience.

What are the ways to protect their rights?

The panel of foster parents from different religious and cultural backgrounds offered a powerful alternative for the foster care system to adopt. The foster care system does not need uniformity that strips children of their religious and cultural identity. The system needs a united commitment to creating environments that maintain children’s connection to their cultural and religious background and community. Children whose lives have been uprooted need their identity, including their faith, language, traditions, and daily rituals, to be preserved. If leaders from vastly different faiths can find common ground in raising children with compassion and purpose, then so can the institutions entrusted with their care by the government.

Cultural and religious competence should be the standard, not a luxury or afterthought.

As I am working on my article, another sad child’s story comes to my attention. A Muslim teen boy, a refugee from Iran, was placed in a loving and experienced home of Mexican descends. Three days later, the boy demanded to be removed because most of the family’s meals contained pork, and they attended church every Sunday. It was not something this boy was used to or was ready to accept. It, in essence, offended his core religious principles.

Agencies and foster parents alike must start with the right questions:

- What are this child’s customs?

- What brings them comfort?

- What can cause a trigger or unnecessary trauma?

- What does their faith look like, if any?

The purpose of cultural and religious understanding and competence is not about forcing foster parents to adopt a child’s religious beliefs and cultural practices, but rather to encourage foster parents to create environments that respect and accommodate a child’s religious beliefs and cultural practices.

I have firsthand experience with the importance of cultural belonging, religious tolerance, and the challenges of adjusting to new environments. I am a Jewish woman, born in Ukraine, shaped by three countries, three cultures, and countless lessons on resilience.

As a child in Soviet Ukraine, I learned early what it meant to be different. I wore it on my skin and carried it in my soul. I faced relentless antisemitism and persecution. Being Jewish was not just my identity; I was a target.

At 17, I moved to Israel, a land of promise. My early years were not easy. I struggled with a new language, unfamiliar customs, and the mix of modern and ancient traditions influenced by ancient Judean culture and the numerous diasporic Jewish practices from across the globe.

The Mediterranean culture—fast-talking, direct, emotionally raw—was a world away from the cold caution of Soviet life. It was my trial by fire.

Moving to California was my third chapter. Life in the U.S. brought yet another cultural shift, but by then, I had developed something invaluable: adaptability. My Soviet childhood made me strong, my years in Israel taught me how to survive in a melting pot, and here, in America, I was ready to connect.

I have developed the ability to find common ground with people who seem, at first glance, entirely different from each other. I approach everyone with my visor up because I believe that shared humanity is always there.

Let’s join forces and collaborate, much like these three remarkable individuals captured in the photograph I took.

It is April of 2025. The moment I’ve been working toward, speaking about, and pushing for is finally here. Thank you!

© [Ana E Tzubery], [2025]. All rights reserved.

This article is the original work of the author and may not be reproduced, published, or distributed without written permission